Danton Remoto is a writer, educator, media personality, and the founder of Ladlad, the LGBTQ political party of the Philippines. His novel, Riverrun, about a gay young man’s coming of age in a military dictatorship, is one of the first gay novels — if not the first gay novel — published in the Philippines. Originally published in 2015, a newer global edition is now being printed by Penguin Random House SEA.

Over several days through email, I had the privilege of interviewing Danton Remoto and share here his words on LGBTQ2IA+ advocacy, Philippine politics, and the literary choices that shape his novel:

Cabahug: Some truly bleak events occur in Riverrun, and the characters grieve after losses, illnesses, calamities, accidents. And yet, there’s also a lot of levity, an enduring humorousness in spite of the tragedies. Might you speak a bit about the importance of the light-hearted and comic touches in your writing?

Remoto: My parents came from the Bicol Region in Central Philippines, a region blessed with fertile land because of the occasional eruption of Mayon Volcano, which has an almost perfect cone. Ten strong typhoons also cross this region every year, leaving devastation in its wake. So if it’s not a volcanic eruption, it will be the floods, an earthquake, and of course, the other calamities caused by the madness of Philippine politics. But my parents, my relatives, people I grew up with, just shrugged these events off and continued with life after the calamity has passed. They planted rice again, or rebuilt the house, started another small business, all the while cracking jokes and exchanging witticisms.

Cabahug: I read the new edition which will be released by Penguin Random House SEA this year, and I was so excited about the addition of intimate scenes! A timbre of erotic yearning hums throughout Riverrun, which unsurprisingly provokes a lot of shame and denial for the main character, but this new edition adds a growing hopefulness and playfulness to his journey. These sections made me smile and laugh. I was wondering if you can speak more about these expansions — of possibilities, of settings, of tone — in the new edition.

Remoto: The editor at Penguin SEA wondered why the main character is full of yearning but the sex is unconsummated, or there is no attempt to initiate it or take part in it. I explained to her that the setting is 1970s-1980s Philippines, a deeply Catholic and conservative society, where gay sex and relationships were frowned upon. She said, all right, but adding at least two sex scenes, she said, would be good for the novel. So what I did was I retrieved a short story that I had written set in a gay bar in Scotland and revised it for this novel. I also wrote a satire on sex, which follows the chapter on a gay bar in Scotland. I called it ‘Fear of Flying,’ after the best-selling erotic book of Erica Jong published in 1973. I called my chapter ‘Fear of Flying’ and readers will understand why after they read that chapter in my novel.

Cabahug: One of the things I absolutely found delightful in Riverrun is the inclusion of legends, ghosts, spectres and creatures from mountains and lakes; I was reminded of the stories I’d heard growing up in the Philippines. Can you speak about your decision to feature mythological storytelling and the supernatural garnishes in this novel?

Remoto: Oh, the woman living in the lake was the reason cited by the Philippine Navy frogman who rescued my dead classmates in the gloom of that lake. So this came from a real story. And the creatures of lower mythology were such an important part of my childhood and upbringing. My father always told us to be home before the spirits came out at 7 PM. My grandmother and my yaya (nursemaid) spun so many tales that until now I can recite even with my eyes closed.

Cabahug: Many scenes of Riverrun — the natural calamities, the plane crash, the beauty queen’s brother — show a preoccupation with the dissonance between what really happened versus the official accounts, between the lived reality of the people versus what’s been distorted and reported in favour of the government. Might you speak a bit more about the political imperative of this novel?

Remoto: I did not want to write a novel that you could watch on television–about a tinpot dictator who is overthrown and a new day begins. If you notice, the dictator and his wife are still there at the end of the novel. When I was growing up in a military airbase at the height of military rule in the 1970s, there were so many things we could not do. We could not leave the airbase, we could not go to school without a military guard armed to the teeth. We could not talk about the many soldiers who would come home from Mindanao, dead or headless, we were told to keep quiet. I wanted to show the dissonance between the official version and the version that happened down there, in the real world, and touched people’s lives, shaping them into lives of sadness or grief. I remember several years ago, someone in the Philippines listed the so-called martial law novel and she did not include mine. I wrote her a letter and said that a careful reading of my book’s Philippine edition will show it is a devastating memoir against martial law.

Cabahug: What’s it like to write about aspects of Philippine culture that are hard to face, hard to accept? And have you gotten feedback from readers who were either taken aback or defensive of how your novel portrayed the governmental corruption, the sanctimonious moralizing, the stigmatization of LGBTQ2IA+ people?

Remoto: The first feedback came from foreigners, because I read chapters of my novel when I was overseas attending writers’ conferences. At Cambridge, after I read at Downing College, the Eastern Europeans came to me and said, with tongue in cheek: “You are just like us. You make fun of our country’s history.” And when I read to American audiences, the Latinos would come to me after and talk to me in Spanish, asking me where is the Spanish original of my novel? And they would be surprised to know that I wrote it in English. What I am saying is that there must be similarities between the cloistered histories and politics of Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Philippines such that these readers saw parallels between my novel and theirs. In the Philippines, someone called me anti-Catholic. Others said that martial law was not so bad, especially for ‘privileged people’ like me who were children of military men. Some defended the leaders of the dictatorship, whose children are still in Philippine politics until now. I just ignore them because what they say does not matter to me.

Cabahug: The novel covers the 60s to the 80s. How much of the Philippine LGBTQ2IA+ experience has remained unchanged even now, at the time of the novel’s release to a global audience?

Remoto: Oh so many things have changed, and I am not saying it is because of me, since I co-edited the gay anthologies Ladlad, founded the political party Ladlad and spoke often on TV and radio about LGBTQ rights. Mass media, popular culture, and the rise of the internet also helped, plus the fact that when people go to college in the cities, they are transported to a milieu that is more open to LGBTQ people. I can only cite the day we watched ‘Brokeback’ Mountain’ in a big mall in the Philippines. It was advertised as an Oscar-award winning film and not a gay film and so many people came. After the two cowboys began kissing, an old woman behind me piped up, talking to her husband: ‘Pedro, Pedro, why are the cowboys kissing?’ And he shushed her up and said, ‘Keep quiet, Maria, maybe the new cowboys can now kiss each other.’ And when we left the theater, I saw boyfriends, wearing identical cowboy clothes, holding hands in the lobby. I just smiled.

Cabahug: How important is LGBTQ2IA+ representation in Philippine literature? And does the literature and media mirror the levels of LGBTQ2IA+ acceptance within the country?

Remoto: I co-edited Ladlad anthologies, which had three books and sold more than 10,000 copies in a country where you’re a bestseller if you have sold 1000 copies of your book. Until now, I write a weekly column for a national newspaper, and this is my 30th year of being a columnist. I also selected some of my columns and published them into books, which I later translated into Filipino. When we began Ladlad, some prominent writers said to the closeted ones, do not submit to Danton, it will destroy your careers. Well, the books became such bestsellers and became part of Philippine Literature. Theses, term papers, and critical essays have been written about Ladlad and our other gay books, both here and overseas. My prominence as a media personality was also the reason I was given a daily TV and radio show, ‘Remoto Control,’ which ran for six, long years. So every night–except during Holy Week and Christmas Day–I was on board talking about Philippine history, current events, arts and culture–and LGBTQ advocacy, in brisk and breezy Filipino.

Cabahug: One of the most distinct aspects of Riverrun is its format, with its vignettes, flash fiction, recipes, and lyrics. How did the form of this novel come to you? What was it like putting together all the disparate sections to tell a cohesive coming-of-age story?

Remoto: I grew up in a household, in a family, in a community, and in a country where people always told stories–while eating, buying something from the street corner store, sitting in the jeepney, waiting to buy tickets for the cinema. But such stories are not always complete. Martial law told us to shut up. Our teachers said that we should be ashamed if we have flat noses and dark skins. Our leaders and their cronies stole from us and foisted festivals, beauty contests, heritage events like so many circuses to cover up for the corruption happening every day. So I decided to cut up the stories. Some of my chapters are very short, 1000 words or less. Recipes figure in some of the chapters, but these recipes are like Greek choruses commenting on the chapters. Songs I included because the Filipino loves to sing, and vignettes are also included, stories heard and repeated to each other, until the shape and form of the fictions have changed. When I was revising the novel, I always put this in my mind: a novel is a story. There should be action. And yet, Milan Kundera’s book, ‘The Art of the Novel,’ helped me as well. This book said that a novel can be composed of chapters that touch only tangentially with your theme. It can be a touch light as a feather, which, by the way, is what some reviewers have described my novel–written with a light touch, even if it deals with such deadly and dangerous things.

Cabahug: Can you speak on the process of writing and publishing this novel? You’ve primarily written poetry and essays. Has that influenced the writing of Riverrun?

Remoto: Some parts of the novel are lyrical, and that you can attribute to the fact that I write poems. The form of the novel is that of a memoir–an older person looks back at the past and remembers them from the frame of the present, so the writing is like that of creative nonfiction. But you must remember that CNF is based on fiction, so the elements of fiction are there: dialogue, setting, scene, plot, narrative arc, closed or open ending. Speaking of ending, this novel lost in the Palanca Grand Prize for the Novel because one of the judges disliked its open ending. The two other judges liked it, but the one who did not like it was the chairperson of the jury. Another reader for a publisher wondered aloud why there was a fairy tale in the middle of the novel? I wanted to tell the publisher, it was a dream sequence, but how do you educate a reader whose concept of fiction is beginning, middle, and end, running in a straight and narrow line?

Cabahug: Was there a moment when you knew you were going to be a writer? How did you discover your authorial voice? What inspires you?

Remoto: When I was young I wanted to paint and write. I had to choose only one because you have to focus. I knew I would write because I read a lot even since I was young–books, comics, the ingredients listed in the noodle-soup packet. I read a lot of Philippine writers in English because I wanted to know the tradition. Of course, I was schooled in the American and British literary canons as well, at universities in the Philippines and the United States when I was a Fulbright Scholar. But I read Philippine writing first, to see what was missing, and that was why I wrote ‘Riverrun.’

Cabahug: Do you see a follow-up to this book, or a revisit to novel-writing for you? What would you like to work on next?Remoto: I was beginning to write a supernatural novel where all the evil people are inspired by Filipino politicians. But then fate intervened, led me by the hand, and told me to write something else–a follow-up to ‘Riverrun’, set in the United States.

Read Frankie Cabahug’s review of Riverrun as part of #GlobalPRIDELitMonth.

Further Reading:

- Read an excerpt of Riverrun on Danton Remoto’s Blog

- LGBT Issues in The Phillipines

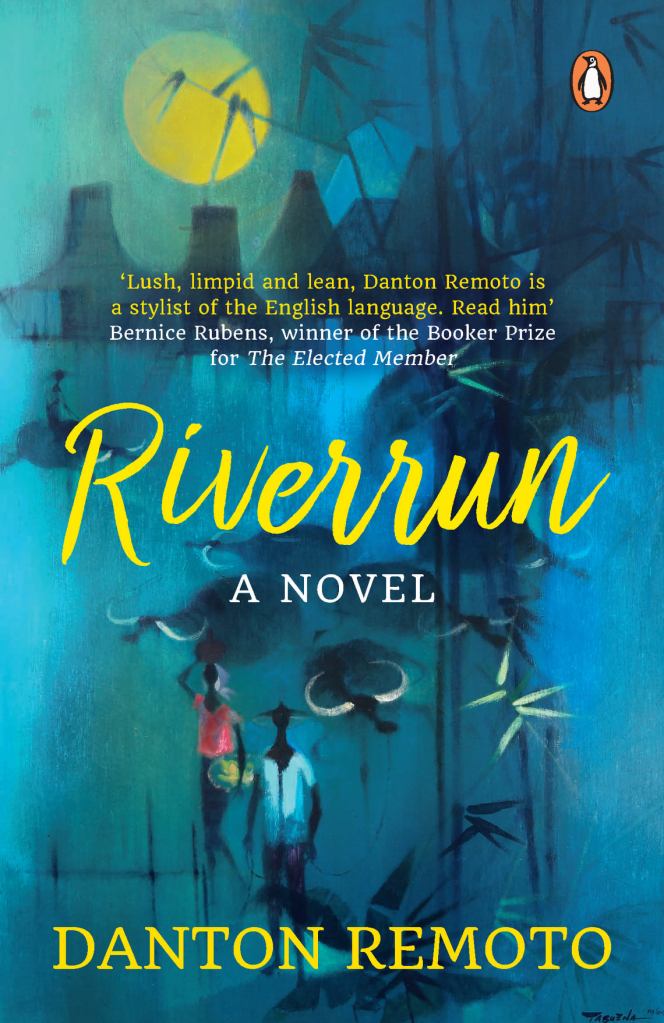

Title: Riverrun: A Novel

Author: Danton Remoto

Original Language: English

Published 2015, Anvil Publishing. New edition forthcoming by Penguin Random House in 2020.

Interviewer: Frankie Cabahug draws and bakes desserts in Vancouver, Canada. She has previously published reviews in The Pacific Rim Review of Books, Sunstar Daily, and Making Waves: Reading BC and Pacific Northwest Literature.

2 thoughts on “#GlobalPrideLitMonth: Interview with author Danton Remoto”